自由意志哲學:笛卡兒從上帝到道德的5個論證

自由意志哲學很多分析面向,本文以笛卡兒《沉思錄》第四卷為主,介紹近代哲學如何透過5個論證,從上帝本質推論到理性道德,帶你瞭解倫理學思辨。

一、笛卡兒第四沉思

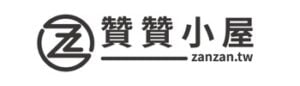

第四沉思的主題是「真與假」,笛卡兒我思故我在的基礎在此繼續思考:既然上帝完美、仁善且不欺騙人,為什麼人仍然會犯錯?他首先指出,錯誤並非一種「真實存在的事物」,而是一種「缺陷」——源自人類有限的本性。上帝賜給人理智與意志,理智讓人認知事物,意志讓人作出選擇。當人類的意志超出理智的範圍,對自己尚未清楚理解的事物妄下判斷時,錯誤便產生。

笛卡兒認為,上帝並沒有給人一種「錯誤的能力」,而是人自己濫用了自由意志。真正避免錯誤的方法,是讓意志的判斷嚴格服從理智的清晰與明證。若我們只對確定明白的事物作出判斷,便永不會被欺騙。

因此,錯誤的責任不在上帝,而在於人如何使用自己的自由。自由意志本身是人最像上帝的部分——無邊且能選擇,但這份自由若不與理性相協調,就會導向誤判。透過這一點,笛卡兒將人類的「有限理性」與「神的完美真理」連結起來,為認識的可靠性建立了倫理與理智的根基。

二、自由意志哲學

自由意志哲學有許多不同的起始點,第四沉思延續前面的基礎,從完美的上帝觀念開始,探討為何會有人類的惡, 分析其中原因,藉此完成一項轉折:以笛卡兒數學演繹方法為主,從「懷疑的哲學」走向「倫理化的理性」,為近代主體哲學建立了理性自我約束的核心。

一、問題的起始點

完美上帝與人類錯誤的矛盾:

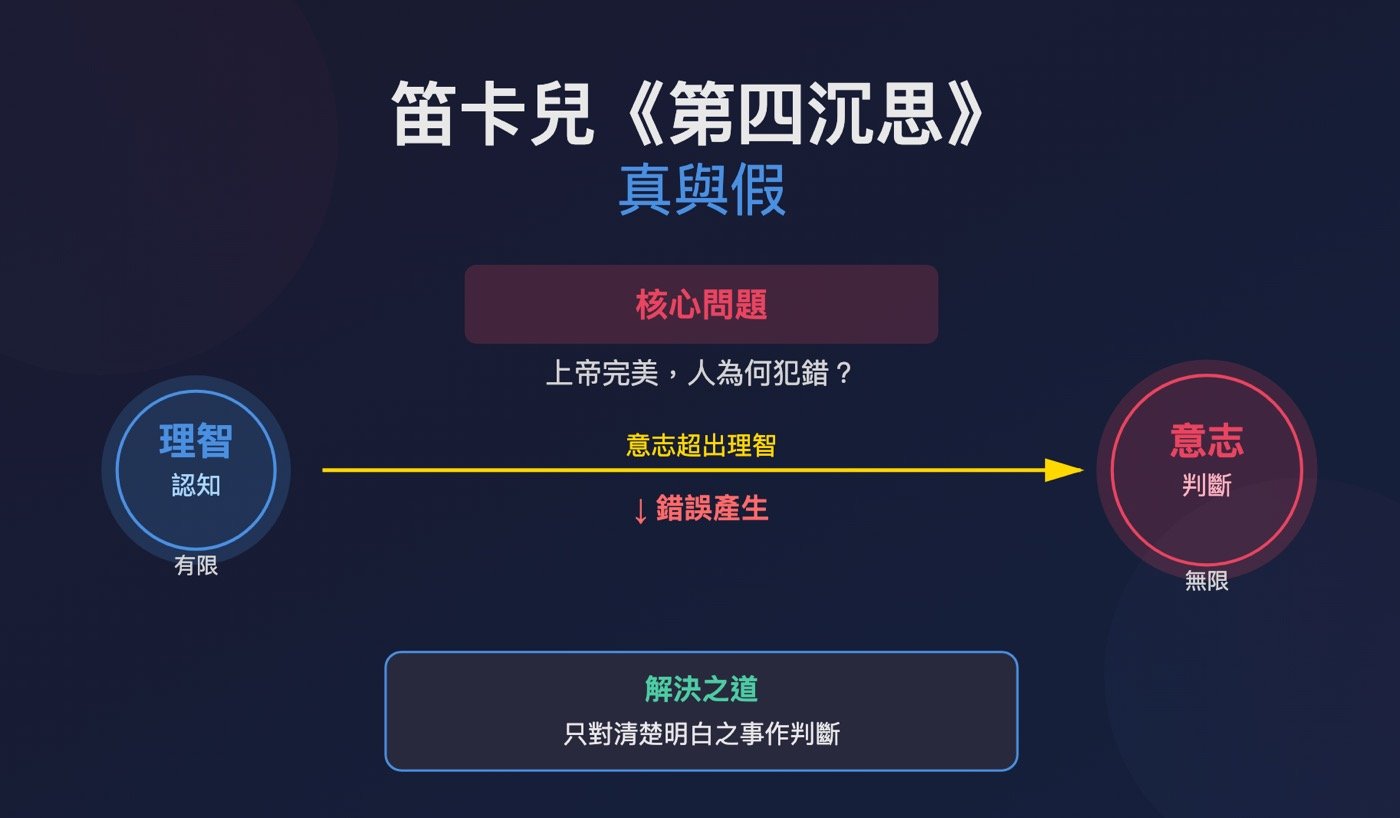

笛卡兒在前三沉思中,已確立兩項確定真理:「我思故我在」與「上帝存在且完美」。然而,若上帝完美且仁善,人作為祂的造物,為何仍會犯錯?這成為第四沉思的核心問題。

笛卡兒首先否定錯誤的「實體性」——錯誤不是一種存在的東西,不是上帝創造的實體,而是一種「缺陷」(privation),象徵有限理性與無限真理之間的距離。

二、理智意志二元論

人性結構的二元來源:

笛卡兒指出,人類的心靈有兩大能力:「理解」(intellect)與「意志」(will)。

- 理智的功能是感知與認識,它的範圍有限。

- 意志的功能是選擇與判斷,它的範圍卻無限。

人類錯誤的根源,正是意志的自由度超過了理智的清晰度。當我們對尚未明確理解的事物做出肯定或否定的判斷,理智之外的部分就被意志誤用,錯誤於焉產生。

三、自由意志的本質

人與上帝的相似性:

笛卡兒認為,人的自由意志是最接近上帝的部分。雖然人類的理智有限,但意志的自由卻無邊無際。上帝的意志與祂的理智永遠一致,故無錯誤;而人的意志若能與理智的清晰明辨相合,也能避免錯誤。

因此,錯誤並非自由的證據,而是自由的濫用。真正的自由,不在於「能選擇任一方向」,而在於「依理性選擇正確的方向」。

四、責任與倫理層面

人必須自負其錯:

笛卡兒在此強調,人不能將錯誤歸咎於上帝。上帝給了人足夠的光明理性,只是人沒有善用。若人能在判斷前確認觀念清晰明確,錯誤將不復存在。這使得理性認識成為一種「倫理責任」:保持審慎、延後判斷,是理性行為的道德實踐。

五、認識論道德哲學

認識論與神學的融合:

第四沉思的思想意義,在於它把「認識的真理性」與「意志的道德性」結合起來。

- 認識論層面:真理來自理智的清晰與明證。

- 神學層面:上帝作為真理之源,不可能欺騙人。

- 道德層面:人需克制意志,使理智與自由達成一致。

三、第四沉思心得

讀《第四沉思》,總覺得它像一面鏡子。那鏡面明亮得幾乎刺眼,映照出人理性最自信的瞬間,也同時暴露出它最無力的陰影。笛卡兒想說明,人之所以會錯,是因為意志太大、理智太小;而上帝之完美,沒有成為欺騙者的空間。聽起來多麼整潔有力,但越往深處想,越覺得那些邏輯縫隙裡,藏著無法填補的小洞。

循環論證的幽靈

笛卡兒說,清楚明白的觀念是真理的標準,因為上帝誠實,不會欺騙我們。但他證明上帝誠實的依據,恰恰又是那些清楚明白的觀念。

理性在這裡像踩著自己的影子起舞,一面依賴上帝保證思維的可靠,一面又以思維去證成上帝的存在,於是落入循環,哲學史上那個著名的「笛卡兒循環」。

它像一種思想上的魔法陣,既穩固又危險——理性在裡頭轉動,卻不一定真的走出了原地。

為何有必要的惡?

笛卡兒承認,人會錯,是因為意志無限,而理智有限。這聽起來像是一種謙卑的解釋,但如果錯誤是因此必然,那麼問題來了——為什麼如此全能的上帝,要創造出一個會錯的存在?

書中給出一個數學定理般的回答:整體的完美性高於部分的完美性。畫家特意在畫布上留下陰影,為了襯托整體的光。

這說法優雅,卻也含糊,它將人的困惑交給「整體」去解釋,彷彿一切不完美,只要放進宇宙的大秩序裡,成了合理。但是對於無數個個體而言,錯誤依舊真實、依舊疼痛,笛卡兒其實沒有真正解決問題。

他畢竟是虔誠的基督徒,繞來繞去,最後總會回歸到上帝,笛卡兒不會以非耶穌的方式回答問題,於是哲學史在等待一個答案。不久之後,終於有個人勇敢站出來,咆哮著喊出「上帝已死」,那是屬於尼采的精神世界。

倫理與認識的界線

笛卡兒把錯誤視為意志的濫用,一種道德上的過失。他純潔的相信,只要克制意志,不對模糊的事物下判斷,人就不會錯。

這是理性最嚴苛的信條——錯誤不是無知,而是放縱。

但我們真的能如此純粹嗎?

知識並不總是明亮的,它往往帶著曖昧與偶然。思考的路上,人不只是理性的存在,也是一個尋路的靈魂。若將錯誤視為罪,或許我們也失去了對迷惘同伴的那份溫柔。

在《第四沉思》裡,笛卡兒我思故我在的辯證繼續推展,想讓理性通往上帝,讓清晰驅散黑暗,可他最終揭示的,卻是理性本身無可救贖的有限。錯誤不只是思維的失誤,更是存在的必然。正因為會錯,我們才必須思考;正因為不完美,真理才值得尋找。笛卡兒一心想尋找顛撲不破的真理,結果卻定追尋者必然錯誤。

四、笛卡兒名言摘錄

在此以《沉思錄》第四卷為主,列出其中較為經典語句,作為笛卡兒名言摘錄。

笛卡兒《第四沉思:真與假》

René Descartes, Meditation IV – Of Truth and Falsehood

一、我由上帝所創造

原文(英)

I recognize that I am as it were something intermediate between God and nothingness, or between supreme being and non-being.

中譯

我明白自己彷彿介於上帝與虛無之間,介於至高存在與無之間的一個中介者。

二、錯誤的根源

原文(英)

Error is not a pure negation, but a privation or lack of some knowledge which should be in me.

中譯

錯誤並非單純的「否定」,而是一種「欠缺」——缺乏某種應該存在於我內的知識。

三、上帝不會欺騙

原文(英)

God is no deceiver; the faculty of judging, which I received from Him, can never lead me into error, provided I use it rightly.

中譯

上帝不是欺騙者;祂賜給我的判斷能力,只要我正確運用,就不會導致錯誤。

四、意志與理智的不平衡

原文(英)

My will is much wider in its range than my understanding; I can affirm or deny far more things than I can clearly perceive.

中譯

我的意志範圍遠大於理智;我能夠肯定或否定的事物,遠超過我清楚理解的範圍。

五、錯誤的起因在於自由意志

原文(英)

When I affirm or deny something without perceiving it clearly and distinctly, I misuse my freedom of choice, and thus I err.

中譯

當我在未清楚明辨之前便肯定或否定某事,我便誤用了自由意志,於是產生了錯誤。

六、自由與責任

原文(英)

The more I incline toward what I clearly perceive as true and good, the more free I am.

中譯

當我越是依循清楚明辨為真與善的事物時,我反而越自由。

七、結論:自由與理性的和諧

原文(英)

True freedom does not consist in being able to choose indifferently, but in being able to follow the intellect without restraint.

中譯

真正的自由,不在於隨意選擇,而在於能毫無阻礙地遵循理智。

五、第四沉思原文

Descartes, Meditation IV – Of Truth and Falsehood)

Lately, I have often withdrawn my mind from the senses, and I have thoroughly considered how few things concerning bodies are truly perceived, while many things concerning the mind, and even more concerning God, are well known. Now, without difficulty, I can turn my thoughts from sensible things to those that are intelligible and abstracted from matter. Indeed, I have a much clearer idea of a human mind, as a thinking thing with no corporeal dimensions—length, breadth, or thickness—than I do of any corporeal object.

Reflecting on myself, I notice that I doubt—that is, I am an imperfect, dependent being. From this, I conceive a clear and distinct idea of an independent, perfect being, which is God. Because I have this idea, I clearly conclude that God exists, and that my being depends on Him at every moment. Nothing can be more evident or certain to human understanding.

I now perceive a method by which, through contemplation of the true God, in whom the treasures of knowledge and wisdom are hidden, I may attain knowledge of other things. First, I know it is impossible for God to deceive me. Deception implies imperfection. Although the ability to deceive might suggest ingenuity and power, the will to deceive indicates malice and weakness, which are not attributes of God.

I have a faculty of judgment, certainly given to me by God. Since He will not deceive me, He has given me the capacity to judge correctly if I use it rightly. I can doubt this truth only if I assume that I could never err—yet when I focus entirely on God, I find no occasion for error. But when I return to contemplating myself, I see that I am prone to innumerable errors. Investigating this, I find that while I have a positive, real idea of God, I also have a negative idea of nothingness. I am created between God and nothing, and because I am not the highest being and lack many perfections, it is no wonder I am deceived.

Thus, error is not a real being dependent on God; it is merely a defect. God did not give me a faculty of error; I err because my faculty of judgment is finite. Error is a privation, a lack of knowledge that ought to be in me. Considering God’s nature, it seems impossible that He would give me any faculty that is imperfect in its kind. The more skillful the maker, the more perfect the work. Could the great maker of all things produce anything not perfect? God can create me so that I am never deceived, yet He may allow me to err for the greater perfection of the universe.

When I consider this more carefully, I realize it is not surprising that God should do things beyond my understanding. I must accept that His nature is immense, incomprehensible, and infinite, while my own is weak and finite. Therefore, many causes are hidden from me. For this reason, final causes are of little use in natural philosophy, for I cannot rashly assume that I can discover God’s designs.

I perceive that whenever we judge the perfection of God’s works, we must consider the whole universe, not individual creatures alone. Something that seems imperfect on its own may, as part of the universe, be most perfect. Although I have doubted everything and discovered nothing certainly to exist except myself and God, I cannot deny that many other things exist or may exist, and I may be part of this universe.

Examining my own errors, I find they arise from two concurrent causes: my faculty of knowing (understanding) and my faculty of choosing (the freedom of my will). By understanding alone, I perceive ideas on which I make judgments, and properly considered, there can be no error. I may lack certain ideas, but this is only a negative absence, not a true deprivation. God does not owe me a greater faculty of knowing. Although He is a skillful creator, He does not need to bestow all perfections on every individual creation.

I cannot complain that God gave me a will greater than my understanding, for freedom of choice consists only in being able to affirm or deny, pursue or avoid, according to my own judgment, without external compulsion. Indeed, the stronger my inclination to one side, the freer my choice. God’s grace and natural knowledge do not reduce my liberty but enhance it. True indifference, where no reason inclines me, is the weakest form of freedom, indicating lack of knowledge. Perfect freedom does not imply indifference.

From this, I perceive that neither the power of willing nor the power of understanding, given by God, is the cause of my errors. My understanding is correct as far as it goes, and my will is fully free. So why do I err? I err because my will extends beyond my understanding. When I make judgments about things I do not fully comprehend, my will, being indifferent to them, easily deviates from truth and goodness, leading to error and sin. For example, when I consider whether anything exists, I find that my own existence is evident. I freely and willingly judge it to be true, guided by the light of understanding. Yet I may encounter doubts about the nature of corporeal things, to which my will remains indifferent, making me capable of error.

If I abstain from passing judgment when I do not perceive truth clearly and distinctly, I act rightly and am not deceived. But if I affirm or deny without clear knowledge, I abuse the freedom of my will, and deception occurs. The privation constituting error arises from my misuse of free will, not from the faculties given by God, nor from God’s concurrence in my actions.

I have no reason to complain that God gave me finite understanding or limited natural light. A finite understanding cannot comprehend all things, and a created understanding must be finite. I should thank God for what He has given me, rather than resent what I never possessed. Likewise, I cannot complain that God gave me a will greater than my understanding. The will is indivisible: to will or not to will. The greater it is, the more I should be thankful to God.

God also concurs in the production of my voluntary actions and judgments, including those in which I err. These acts, as they depend on God, are true and good. Error does not require God’s fault, because it is a privation, not a real thing. My freedom of assent, when applied to things I do not clearly understand, is not an imperfection in God but in me, when I misuse this liberty.

It is possible, however, that God could have enabled me, while remaining free and finite in knowledge, to never err—by endowing my understanding with clear and distinct knowledge of everything I might deliberate on, or by firmly implanting the rule that I must never judge without clear understanding. Either would have made me more perfect. Yet the universe may gain greater perfection if some parts are subject to error. I have no reason to complain that I act as a part of this world, not its chief or most perfect part.

Through continued meditation, I can train myself to follow this rule: to judge only what I clearly and distinctly understand. In doing so, I discover the cause of error and falsehood: whenever I limit my will to what I clearly understand, I cannot err. Clear and distinct perceptions cannot come from nothing—they must come from God, who is infinitely perfect and cannot deceive. Therefore, they are true.

Today, I have learned not only what to avoid to prevent deception but also what to do to discover truth: I must apply myself only to things I perfectly understand and distinguish them from what I apprehend confusedly or obscurely. By this practice, I may cultivate a habit of avoiding error.

贊贊小屋讀書的好處:

諸葛亮故事、莊子的人生哲學、地藏經全文、笛卡兒演繹法、蘇東坡人生態度、西遊記線上看、封神演義線上看、白蛇傳小說線上看、妙法蓮華經功效。

相關文章: