上帝存在論證:笛卡兒如何證明1個上帝的存在

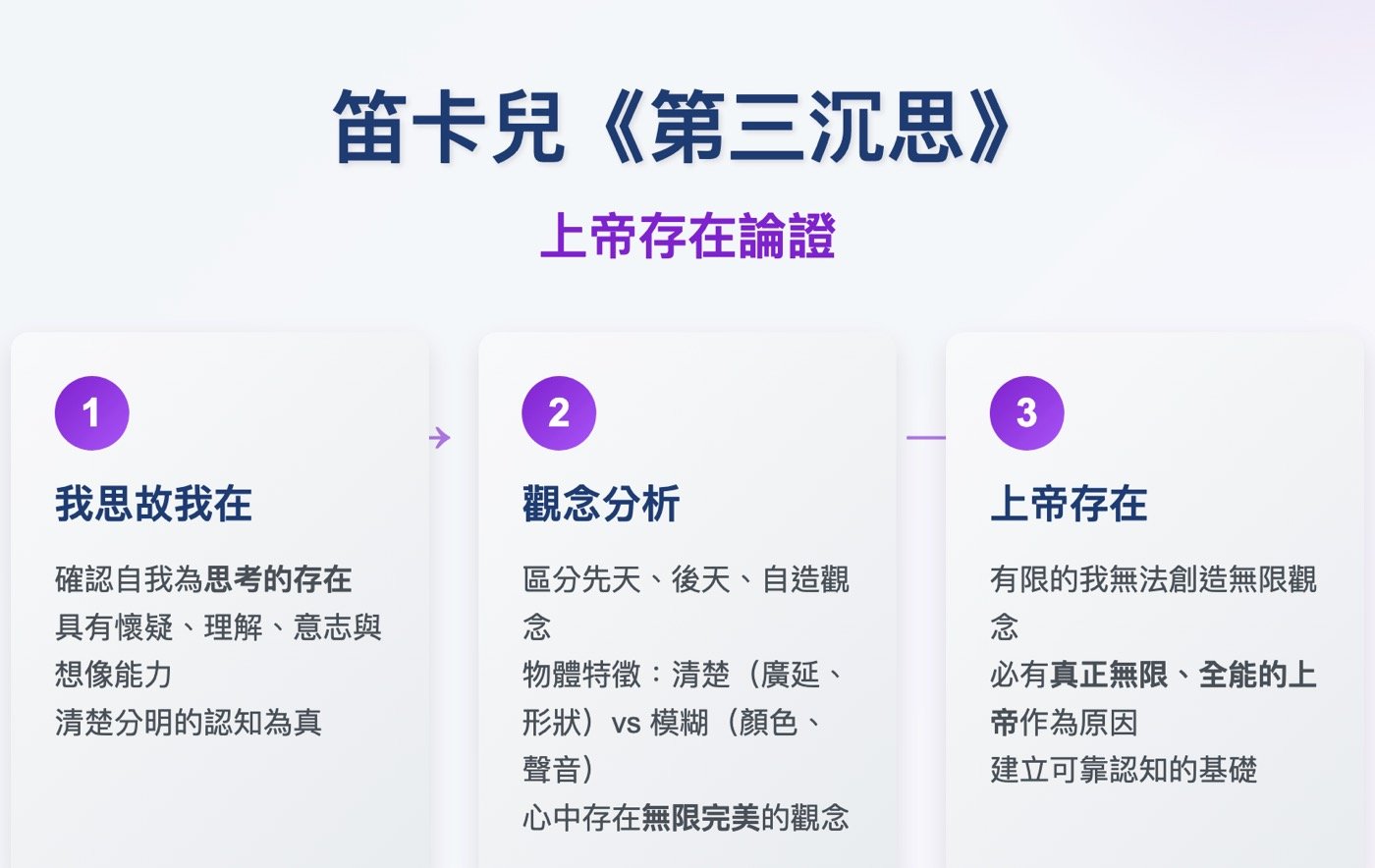

上帝存在論證有許多探討的方式,本文以《沉思錄》中的第三沉思為主,介紹笛卡兒如何應用其演繹法構思,清楚闡述,層層推理,證明1個上帝的存在。

一、笛卡兒演繹法

在《第三沉思》中,以笛卡兒演繹法探討「上帝存在」的問題。他首先將感官印象排除,專注於自我思考,確認自己是一個「思考的存在」,具有懷疑、理解、意志與想像等能力。由於清楚分明的認知必然為真,他尋求可靠認知的基礎。

接著,他分析心中各種觀念(Ideas),區分先天、後天及自造的觀念,指出除自我觀念外,其他事物如物體、天使、人等,是否真的存在仍不確定。對物體的觀念,他認為只有部分特徵如廣延、形狀、運動等是清楚的,其餘如顏色、聲音、溫度等則模糊,可能並非真實。

最後,笛卡兒我思故我在延伸出「上帝觀念論證」:心中存在「無限、完美」的觀念,而他自身有限,無法自創此觀念,因此必須存在一個真正無限、全能的上帝作為其原因。這個推論建立了上帝存在的基礎,並解釋了心中觀念的來源與可靠性。簡單的說,笛卡兒是虔誠的基督信徒,把一切榮耀歸於上帝。

二、上帝存在論證

上帝存在論證揭示人類理性探索的極限與可能。以笛卡兒名言「我思故我在」為基礎出發,歷經魔鬼欺騙的懷疑,正反思維相互碰撞,最終得出上帝存在的結論。他在《沉思錄》第三卷中的論述如下:

上帝存在的雙重論證

- 從觀念的客觀實在性論證:

- 我心中有「無限完美存有」的觀念

- 這觀念的客觀實在性極高

- 我作為有限存有,無法是這觀念的充足原因

- 因此必有一個實際無限完美的存有(上帝)作為原因

- 從自我存在論證:

- 若我能創造自己,我會賦予自己一切完美

- 但我顯然是有限、不完美的

- 所以我不能是自己存在的原因

- 必有上帝創造並維持我的存在

哲學意義

這個論證在笛卡兒體系中至關重要,因為:

- 它從我思的確定性出發,建立上帝存在

- 有了善良上帝的保證,才能確保清楚明晰的知覺可靠

- 從而解決惡魔假設帶來的普遍懷疑

這形成了著名的「笛卡兒循環」爭議:需要上帝保證清楚明晰的認知,但證明上帝存在又依賴清楚明晰的認知。

三、沉思錄的觀點

在此根據《沉思錄》第三卷主要內容,說明笛卡兒推理過程如下:

1. 重新檢視自我觀念

笛卡兒先暫時「關閉感官」,只專注於心靈活動。他確定自己是「一個思考的東西」(思考、懷疑、肯定、否定、想像、感覺),這一點無可置疑。他要檢視心中所有觀念(ideas),看看哪些真實、哪些可能錯誤。

2. 明晰分明的判斷原則

他確認「凡我清楚而分明地感知的,都是真的」這個原則,但也承認自己過去曾誤以為感官對象是真實外物(例如天、地、星辰),卻其實只清楚知道「自己有這些觀念」,並不能確定觀念的來源在外部。

3. 觀念的類別與真實性

他把觀念分成三種:

- 先天(innate):天生的概念(如存在、真理、思想本身)。

- 外來(adventitious):似乎從外界來的(如感官知覺:聽聲音、見太陽、感熱)。

- 自造(factitious):自己組合虛構(如人魚、怪物)。

就算某觀念不由我意志產生,也不能保證它真來自外部;夢境就是例子。

4. 觀念真實性與因果律

觀念本身只是「思維的樣態」,不會真「錯」,錯在於我們對觀念來源的判斷。

笛卡兒主張:效果中的現實必須至少在原因中有對應的現實。

這不只適用於實在物(如石頭不能無中生有),也適用於觀念的「客觀實在性」(objective reality)。如果我有一個包含「無限、全能、全知」的上帝觀念,而這些屬性在我這有限存在中不存在,那麼這觀念必須來自一個真正擁有這些屬性的存在。笛卡兒數學素養在此得到很好的應用,以理性演繹的方法推論上市的存在。

5. 推論至上帝的存在

因此,當我檢視各種觀念時,發現「上帝」的觀念有最豐富、最高度的「客觀實在性」,而這種觀念不可能由我有限的心靈自生或組合出來,必然有一個真正的「無限存在」作為原因。於是,笛卡兒由「觀念的因果律」推出:上帝必然存在。

四、第三沉思原文

Meditation III: Of God, and That There Is a God

Now I will close my eyes, stop my ears, and withdraw all my senses.

I will erase the images of corporeal things from my mind—or, since that is hardly possible, I will simply pay no attention to them, regarding them as vain and false. By reflecting on myself and examining my own nature more carefully, I will strive gradually to become more familiar with myself.

I am a thinking thing—that is, a being that doubts, affirms, denies, understands some things, remains ignorant of many things, wills, refuses, imagines, and is also sensitive. As I noted before, although whatever I imagine or sense may not exist outside me, the manner of thinking I call sense and imagination—since they are merely modes of thinking—certainly exists in me. In these few words, then, I have mentioned all that I know, or at least all that I presently perceive myself to know.

Next, I will examine more carefully whether there is something else in me of which I have not yet taken notice. I am certain that I am a thinking thing; yet how can I be certain of anything else? My answer is that my first knowledge consists only of clear and distinct perceptions of what I affirm. But such perceptions alone would not suffice to guarantee the truth of a thing if it were possible that something I perceive clearly and distinctly could be false. Therefore, I may establish this as a principle: whatever I perceive clearly and distinctly is certainly true.

Yet in the past I admitted many things as very certain and obvious, only to later find them doubtful. What were these things? The heavens, the earth, the stars, and all other things I perceived through my senses. But what did I perceive clearly about them? I perceived only the ideas or thoughts of these things in my mind. And I cannot deny that I currently have these ideas. But I also affirmed something else, which, by common belief, I thought I perceived clearly—namely, that there are certain things outside me from which these ideas proceed, and to which they correspond exactly. In this, I was either deceived, or, if by chance I judged truly, my perception was not strong enough to guarantee it.

When I consider a simple and easy proposition in arithmetic or geometry, such as that two plus three equals five, do I not perceive it clearly enough to affirm it as true? Indeed, I have no reason to doubt these truths except that I think there may be a God who could have created me so that I am deceived even about things that appear most clear. Whenever I consider God’s great power, I cannot deny that he could cause me to err even in things that seem most evident. Yet when I reflect on the things themselves, which I judge I perceive clearly, I am fully convinced by them. I am compelled to say: let anyone attempt to deceive me, yet they cannot make it true that I do not exist while I think, “I am,” nor that two plus three make anything other than five. In these matters, I perceive a manifest contradiction.

Seeing that I have no reason to consider any God a deceiver, and not yet fully knowing whether there is a God, this doubt is slight and metaphysical, depending only on an opinion I am not yet convinced of.

Therefore, to remove this obstacle, I must inquire whether there is a God, and, if so, whether he can be a deceiver. Until I know this, I cannot be fully certain of anything else.

Now, the method seems to require me to classify all my thoughts under certain categories and to investigate which of them truly contains truth or falsehood. Some thoughts are, as it were, images of things, and to these alone the name “idea” properly belongs—such as when I think of a man, a chimera or monster, heaven, an angel, or God. Others, however, have superadded forms, as when I will, fear, affirm, or deny. Whenever I think, I always have some object or subject of thought; but in these latter kinds of thoughts, there is something more than merely the likeness of the thing. Among these, some are called wills and affections, and others are called judgments.

As for ideas themselves, considered alone, without reference to anything else, they cannot properly be false. Whether I imagine a goat or a chimera, it is equally certain that I imagine one or the other. Likewise, in the will and affections, there is no falsehood to fear. Even if I wish for evil things, or things that do not exist, it is still true that I wish for them.

Therefore, the only place in which error can arise is in my judgments about things. The chief and most common error I find is that I judge the ideas within me to conform to certain things outside me. Truly, if I consider these ideas merely as modes of my thought, without regard to anything external, they hardly give me any opportunity to err.

Some ideas are innate, some are adventitious, and some appear to me as if created by myself. For instance, my understanding of what a thing is, what truth is, or what a thought is, seems to arise purely from my own nature. But when I hear a noise, see the sun, or feel heat, I have always judged that these sensations come from external things. Finally, creatures such as mermaids, griffins, and other monsters are made purely by myself. Yet I may consider any of these ideas as adventitious, innate, or self-created, since I have not yet discovered their true origin.

I should focus especially on those ideas I count as adventitious, which I consider to come from external objects, so that I may determine the reason for thinking them like the things they represent. Nature teaches me this, and I know that these ideas do not depend on my will, and therefore not on me. They often appear despite my inclinations—for example, whether I will it or not, I feel heat. Therefore, I conclude that the sense or idea of heat is caused by a thing really distinct from myself—namely, the heat of the fire before which I sit. It is natural, then, to judge that the thing itself transmits its own likeness to me, rather than some other thing being transmitted in its place. Whether these arguments are strong enough, I shall now try to examine.

When I say that “nature teaches me so,” I mean only that I am, as it were, willingly compelled to believe it—not that it is revealed to me as true by any natural light. These two differ greatly. Whatever is revealed to me by the light of nature—for example, that it necessarily follows that I exist because I think—cannot possibly be doubted. I have no faculty in which I may place as much confidence as in the light of nature, nor any faculty that could convince me that what the natural light teaches me is true is actually false. As for my natural inclinations, I have often found that I am misled by them into choosing the worse of two goods. Therefore, I see no reason to trust them in any other matters.

Even though these ideas do not depend on my will, it does not necessarily follow that they originate from external things. Just as the inclinations I mentioned earlier are distinct from my will, perhaps there is another faculty within me—currently unknown—that may be the efficient cause of these ideas. For example, I have observed ideas forming in me while I dream, without the aid of any external object.

Even if these ideas do come from things distinct from me, it does not follow that they must resemble those things. Often I have found the idea and the thing to differ greatly. For instance, I have two different ideas of the sun: one derived from my senses, which I classify as adventitious, by which it appears very small; another derived from the reasoning of astronomers or from other natural considerations, by which it appears much larger than the Earth. Certainly, both of these cannot resemble the sun itself, and reason persuades me that the idea derived immediately from the sun is the least like it.

These observations show that I have so far believed in the existence of things outside me—not based on true judgment, but from a blind impulse—that transmit their ideas or images to me via the senses or by some other means.

I can, however, inquire further into whether any of the things corresponding to my ideas really exist outside me. Ideas are merely modes of thinking, equal in themselves, all proceeding from me in the same manner. Yet some ideas represent substances, while others represent only modes or accidents. It is clear that ideas representing substances possess more objective reality than those representing mere modes, and the idea by which I conceive of a mighty, eternal, infinite, omniscient, and omnipotent God contains even more objective reality than ideas of finite substances.

By the light of nature, it is evident that the total efficient cause must contain at least as much reality as its effect. An effect cannot possess more reality than its cause. Hence, a thing cannot be created from nothing, nor can something more perfect originate from something less perfect.

This principle applies not only to effects in which we consider actual or formal reality, but also to ideas in which only objective reality is considered. For example, it is impossible for a stone to begin to exist unless produced by something that contains formally or virtually all that goes into making the stone. Similarly, heat cannot be produced in anything not already capable of it, except by a cause at least as perfect as heat itself. Likewise, my idea of a stone or heat must be placed in me by a cause containing at least as much reality as the idea represents. Even though the cause does not transfer its actual or formal reality into my idea, I cannot conclude the cause is less real; rather, the idea itself is a mode of thought.

Thus, the objective reality of an idea requires a cause in which at least as much formal reality exists as there is objective reality in the idea. If anything in the idea were not in its cause, it would come from nothing. Even though the idea exists only objectively in the intellect, it is not nothing and cannot proceed from nothing.

Therefore, the reality I perceive in my ideas—though only objective reality—implies that their causes must formally contain at least that much reality. The objective mode of being belongs to the nature of the idea itself, while the formal mode of being belongs to the nature of the cause of ideas, particularly the first and chief causes. Though one idea may derive from another, we cannot go on infinitely; at last, there must be a first idea, whose cause is an original model containing formally all the objective reality of the idea.

By the light of nature, I thus clearly perceive that the ideas in me are like pictures that may fall short of the perfection of the things from which they are taken, but cannot contain anything greater or more perfect than them. The more diligently I examine these matters, the more clearly and distinctly I recognize their truth.

But what should I conclude from this? If the objective reality of any of my ideas is such that it cannot be contained in me either formally or eminently, so that I cannot be its cause, it necessarily follows that not only do I exist, but that there also exists some other thing which is the cause of that idea.

If, however, I can find no such idea within me, I have no argument to persuade me of the existence of anything besides myself. I have diligently inquired and so far discovered no other persuasive evidence.

Among the ideas I possess (besides the one that represents myself to myself, which is beyond doubt here), there are some that represent God, others that represent corporeal and inanimate things, some angels, others animals, and lastly some that represent men like myself.

As for the ideas representing men, angels, or animals, I can easily understand that they might be composed out of the ideas I already have of myself, of corporeal things, and of God, even if no man (but myself), no angel, and no animal actually existed.

With respect to the ideas of corporeal things, I find nothing in them of such perfection that it could not arise from myself. If I examine them more closely, as I did yesterday with the idea of wax in the Second Meditation, I find that there are very few features which I perceive clearly and distinctly in them: namely magnitude or extension in length, breadth, and depth; figure or shape arising from the termination of extension; position or place relative to other figured bodies; motion or change of place. To these may be added substance, duration, and number.

As for the remaining qualities—such as light, colors, sounds, smells, tastes, heat, cold, and the other tactile qualities—I have only obscure and confused thoughts of them. I cannot tell whether they are true or false: that is, whether the ideas I have of them correspond to things that really exist or not. Although formal and proper falsity consists only in judgment (as I have already observed), there is another sort of material falsity in ideas, when they represent something as really existing though it does not exist. For example, my ideas of heat and cold are so obscure and confused that I cannot tell whether cold is merely the privation of heat, or heat the privation of cold, or whether either is a real quality, or neither is. Since every true idea must resemble the thing it represents, if it is true that cold is nothing but the privation of heat, then an idea which represents it as a real positive thing may rightly be called false. The same applies to other such ideas.

Therefore, I see no necessity to assign any author of these ideas but myself. If they are false, representing things that are not, I know by the light of nature that they proceed from nothing—that is, I entertain them merely because my nature is deficient and imperfect. If they are true, yet since I discover so little reality in them that it scarcely seems real at all, I see no reason why I myself should not be their author.

Even some of the ideas of corporeal things which are clear and distinct might seem borrowed from the idea I have of myself: for example substance, duration, number, and the like. When I conceive a stone as a substance—that is, as something apt to exist by itself—and also conceive myself as a substance, though I conceive myself as a thinking substance not extended, and the stone as an extended substance not thinking, there is a great difference between the two conceptions, yet they agree in being substances. Likewise, when I conceive myself as now existing and also remember that I have existed before, and since I have diverse thoughts which I can number or count, from this arises my notion of duration and number, which I then apply to other things.

As for the other elements out of which the idea of a body is composed — extension, figure, place, and motion — they are not in me formally, since I am only a thinking thing. Yet because they are merely certain modes of substance, and I myself am also a substance, they may seem to be in me eminently.

Thus there remains only the idea of God. Here I must consider whether it contains anything which could not possibly have its origin in me. By the word God I mean an infinite substance, independent, omniscient, omnipotent, by whom both I myself and everything else that exists (if indeed anything does exist) was created. All these attributes are of such an exalted nature that, the more attentively I reflect upon them, the less I can conceive myself to be the author of these notions.

From what has been said, I must conclude that there is a God. For although the idea of substance might arise in me because I myself am a substance, I could not have the idea of an infinite substance (since I myself am finite) unless it proceeded from a substance which is truly infinite. Nor ought I to suppose that I have no true idea of infinity, or that I perceive it merely by the negation of what is finite, as I conceive rest and darkness by the negation or absence of motion or light. On the contrary, I plainly understand that there is more reality in an infinite substance than in a finite one, and therefore the perception of the infinite (as God) is prior to the notion I have of the finite (as myself). For how should I know that I doubt or desire—that is, that I lack something and am not wholly perfect—unless I had the idea of a being more perfect than myself, by comparing myself with which I recognize my own imperfections?

Nor can it be said that this idea of God is materially false, and so proceeds from nothing, as I observed earlier of the ideas of heat and cold. On the contrary, since this notion is most clear and distinct, and contains in itself more objective reality than any other idea, none can be more true in itself or less suspect of falsity. The idea (I say) of a being infinitely perfect is most true, for although it may be supposed that such a being does not exist, it cannot be supposed that the idea of such a being presents to me nothing real, as I said before of the idea of cold. This idea also is most clear and distinct, for whatever I perceive clearly and distinctly as real, true, and perfect is wholly contained in this idea of God.

Nor can it be objected that I cannot comprehend the infinite, or that there are innumerable other things in God which I can neither conceive nor even think about. It belongs to the very nature of the infinite not to be comprehensible by me, a finite being. It is enough for me to prove that this idea of God is the most true, clear, and distinct of all the ideas I have, because I understand that God is not to be fully understood, and because I judge that whatever I clearly perceive and know to imply perfection—and perhaps innumerable other perfections of which I am ignorant—are in God either formally or eminently.

But perhaps I am something more than I take myself to be, and perhaps all those perfections which I attribute to God are potentially in me, though at present they are not manifest and active. For I know from experience that my knowledge can increase, and I see nothing that prevents it from increasing indefinitely, nor why by such increased knowledge I might not attain the other perfections of God, nor finally why the power or capacity of having these perfections might not be sufficient to produce the idea of them in me.

Solution. None of these alternatives suffice. For although it is true that my knowledge can be increased, and that many things are in me potentially which actually are not, none of these can generate the idea of God, in which I conceive nothing potentially. It is a clear sign of imperfection that something may be gradually increased. Furthermore, although my knowledge may grow, it can never become actually infinite, for it can never reach that height of perfection which admits no higher degree. Yet I conceive God to be actually infinite, such that nothing can be added to his perfections. Lastly, I perceive that the objective being of an idea cannot be produced solely by the potential being of a thing (which is in proper speech nothing), but requires an actual or formal being for its production.

All these things are evident to anyone who considers them carefully. Yet, because I am sometimes careless and the images of sensible things blind my understanding, I must further enquire whether I, who have this idea, could possibly exist unless such a being actually existed. From what source could I be? From myself? From my parents? Or from any other being less perfect than God? For nothing can be imagined as more perfect or equally perfect with God.

If I were from myself, I should neither doubt, nor desire, nor want anything, for I would have endowed myself with all the perfections of which I have any idea, and consequently I myself would be God. Yet I perceive lack and imperfection in myself. It is manifest that it is far more difficult for a thinking substance to arise from nothing than to acquire knowledge of things I do not yet know, which are mere accidents of my substance. If I had the greater being (viz., my existence) from myself, I would not have denied myself those perfections perceived in the idea of God. For if something were truly more difficult, it would also seem more difficult to me, yet it does not.

Nor can I escape this argument by supposing that I have always been as I am, and so need not seek an author of my being. The duration of my life may be divided into innumerable parts, each not depending on the others. Therefore, it does not follow that because I was a moment ago, I must now exist. The continuation of my existence requires, at each moment, the same power and action as creation itself. Hence, the act of conservation differs from the act of creation only in reason, as philosophers term it.

Wherefore I must ask myself this question: do I, who now exist, have any power to cause myself to exist hereafter? For if I had such power, I would certainly know it, since I am nothing but a thinking thing—or at least, for now, I treat only of that part of me which thinks. I find no such power in myself; and thus I clearly know that I depend on some other being distinct from myself.

But suppose I claim that this being is not God, but that I am produced either by my parents or by some other causes less perfect than God. To answer this, I recall (as I said before) that it is manifest that whatever is in an effect must at least be present in its cause. Since I am a thinking thing and have in me an idea of God, it follows that whatever cause I assign of my being must itself be a thinking thing, possessing an idea of all those perfections I attribute to God.

Then we may ask of that cause whether it is from itself or from another cause. If it is from itself, then (as has been shown) it must be God. For since it has the power of existing by itself, it also undoubtedly has the power actually to possess all those perfections of which it has an idea—that is, all the perfections I conceive in God. If it is from another cause, then we must ask the same question of that cause, and so on, until we arrive at the first cause of all, which must be God. This inquiry cannot proceed to infinity, especially since I am not only treating of the cause which first made me but of the cause which conserves me in existence at this present moment.

Nor can it be supposed that many partial causes combined to make me, giving me the idea of one divine perfection from one source, another from another, and so forth, with all these perfections scattered in the world but not united in any single being that may be God. On the contrary, unity, simplicity, and the inseparability of all God’s attributes is one of the chief perfections I conceive in Him. Certainly, the idea of the unity of divine perfections could not be produced in me by any cause other than the one from which I received the ideas of His other perfections. It is impossible to make me conceive these perfections as conjoined and inseparable unless the same cause also made me know what perfections they are.

Finally, as to my having my being from my parents: even if all my former thoughts about them were true, they certainly contribute nothing to my continued existence. Nor do I proceed from them inasmuch as I am a thinking thing, for they only prepared that material body in which I—that is, my mind, which I presently take to be myself—resides. Therefore I cannot now seriously question that I spring from them. I must necessarily conclude that, because I exist and because I have an idea of a most perfect being—that is, of God—it evidently follows that God exists.

Now it only remains to examine how I have received this idea of God. I have not received it through my senses, nor does it come to me unbidden as do the ideas of sensible things when such objects act (or seem to act) upon the organs of my senses. Nor is this idea fabricated by myself, for I can neither subtract from it nor add anything to it. I must conclude, then, that it is innate, just as the idea of myself is natural to me.

Nor is it surprising that God, in creating me, should imprint this idea upon me so that it remains as a stamp impressed by the craftsman God upon me, his work. It is not necessary that this stamp be a thing different from the work itself. It is highly credible, simply from the fact that God created me, that I am made in some way according to his likeness and image; and that the same likeness in which the idea of God is contained is perceived by me with the same faculty by which I perceive myself. That is to say: when I reflect upon myself, I perceive not only that I am an imperfect being dependent on something else, and that I am a being who desires more and better things without limit; but also, at the same time, I understand that the one on whom I depend contains in himself all those desired things, not only indefinitely and potentially but really and infinitely, and that therefore he is God.

The whole force of the argument lies here: it is impossible that I should be of the nature I am—namely, having within me the idea of God—unless God really existed, that very same God whose idea I have in my mind: the one possessing all those perfections which I cannot fully comprehend but can at least think about, and who is subject to no defects.

From this it is evident that God is no deceiver. For it is manifest by the light of nature that all fraud and deception depend upon some defect. But before pursuing this further, or prying into other truths that may be deduced from it, I am willing here to pause and dwell upon the contemplation of this God: to consider within myself his divine attributes, to behold, admire, and adore the beauty of this immense light as far as my dark understanding will allow. For just as by faith we believe that the greatest happiness of the next life consists solely in the contemplation of the divine majesty, so too we find by experience that even now we receive from this contemplation the greatest pleasure of which we are capable in this life, though it is much more imperfect than that of the next.

贊贊小屋讀書的好處:

地藏經全文、笛卡兒演繹法、蘇東坡人生態度、西遊記線上看、封神演義線上看、白蛇傳小說線上看、妙法蓮華經功效。